We saw how money helps in exchanging goods & services in this article. But what do our exporters do when they have to deal with buyers in countries that have their own money, issued by a different institution than ours, with a different guarantor than the one we trust.

Obviously the simplest way for an exporter is to quote a price in the currency of his home country. But it should be acceptable to the buyer (importer), for whom her home currency is different.

Why would a buyer or a seller hesitate to deal with currency which is not their home currency? Is it trust in a currency? Or is it a more practical consideration. There are two simple reasons which we will see below.

1. Stability: Imagine a carpet exporter in Turkey who prices a particular variety of carpet at 100 TRY (Turkish Lira) apiece when he sells within his own country. He would like to charge the same when he exports them too. As long as he quotes the price in TRY, there is no currency risk for him. But let’s assume the importer — who lives in Egypt- prefers not to pay in TRY and wants to pay only in EGP (Egyptian Pounds). Our exporter submits a quote in mid Dec 2021, where the exchange rate between the two currencies was 1 EGP = 1 TRY. So the carpets will be quoted at 100 EGP (which would have translated to 100 TRY). This looks simple. But we need to understand currencies can be volatile, (i.e the extent to which exchange rate varies on a given day is high). Below is a chart of exchange rate between EGP and TRY for the past one year. (Credit: xe.com)

Now, international trade doesn’t happen in an instant. Importers seek quotes from various exporters across countries, take their time to evaluate and then place the order. Suppose our importer in Egypt wants to place an order in mid-Jan 2022. The importer would be willing to pay only 100 EGP as that was the quoted price per carpet.

As we can see from the chart above, the exchange rate between EGP and TRY changed in Jan 2022 to 1EGP = 0.70 TRY when the deal is signed. Now if the payment were to happen immediately, our Turkish exporter would have got only 76 TRY for each of his carpets instead of 100 TRY, thereby incurring a loss if he goes ahead with the deal. All because the exchange rate was very volatile.

So just quoting the price for the order in a volatile currency is very difficult for the exporter (& to the importer if the opposite had happened). However if they were to agree to price the goods in a more stable currency, where the volatility is less, it brings some stability in the trade process. So exporters around the world want to quote the price of their goods in currencies that are less volatile. Let’s call this stable currency, XYZ for now.

2. Exchange rate risk. Let’s say our exporter “receives a confirmed order”. This means he has locked in his price in a (relatively) stable currency XYZ. This does not completely eliminate his price risk. International trade usually has a time lag between the time an order is placed and the final payment is made (more on the why in a later article) — say 3 months. There is every chance that the exchange rates between XYZ — TRY and XYZ — EGP changes in these 3 months. But this exchange rate risk can be mitigated by both the exporter and the importer by taking out currency forward contracts with their respective banks. The bank will charge a fee for this, but this mitigation gives certainty to both the importer (on how much she has to pay) and the exporter (on how much he will receive) in their respective local currencies.

A question can come in your mind, if exchange rate risk can be mitigated for a fee, why not do it at the time the quote was prepared, i.e in Dec 2021 itself? We need to remember, in Dec, there was no certainty that the importer will accept the order; so there is no cash flow expected to cover the risk. Whereas in Jan once the deal is signed, there is a contractual obligation for the importer to pay and certainty on a certain amount to be paid and received.

There will be volatility between any two currency pairs but the extent of volatility will be less if one of the currencies is a stable currency (XYZ).

Enough of talking in variables, what happens in real lives? What is the stable currency in which most trade happens in the real world? Most trade is quoted in USD (the reasons are long but the undeniable fact is, it is a currency backed by the US govt and trusted by almost the entire world to be relatively stable). A few other currencies also enjoy this trust, (EUR, GBP, JPY & CHF) but not to the extent of USD.

Lets see how the two currencies performed w.r.t USD. Below are one year historical charts of exchange rates.

First between USD and TRY. Credit: xe.com

The chart looks almost similar to the EGP TRY chart, indicating that it was TRY which had had a volatile year.

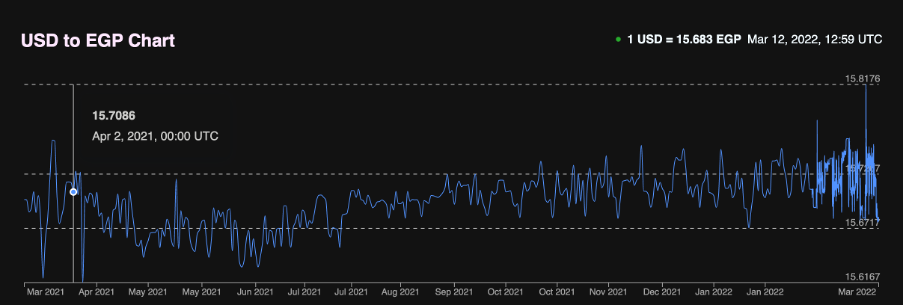

Now, if we see the exchange rate between USD and EGP in the same period, it looks like this. Credit: xe.com

The chart looks volatile but within a very narrow band. So most of the exchange rate volatility between EGP — TRY was due to high volatility of TRY and moderate volatility of EGP.

3. Fungiblity of the trade currency. While all money is fungible in theory, it has boundaries. Real fungibility happens only when the earned currency can be ‘used’ to purchase any other goods / services from a different country. Assume that our exporter quotes his goods in EGP to his Egyptian client and also receives EGP upon sale. He will now have EGP funds with him. Unless he has to buy something quoted in EGP (most likely from Egypt), he has to convert his EGP into a third currency. Take for instance that he needs to buy weaving machines from a vendor in Germany, his EGP will be of no use and he has to convert EGP to EUR which involves transaction costs and fees to bank (even if we ignore currency volatility for a moment). So exporters and importers, prefer to have a single currency that is acceptable by traders across borders.

4. Government diktat. Yes, as part of managing the economy, governments also dictate — for good reason- what currencies their international traders can deal in. This is because, governments, primarily through their central banks maintain what is called “Foreign currency reserves”, to ensure they have adequate currency to pay for their countries’ imports. Central banks cannot be holding (& maintaining) a balance in several currencies like EGP, TRY and may prefer to hold only in certain currencies (like USD, EUR, JPY etc.) that are not very volatile. (None of us would want to hold an asset ( a reserve) whose value is volatile isn’t it). Due to this, any importer or exporter of a particular country are allowed by their governments to trade in only a few currencies. Purists might want me to tell you about the gold standard, the Bretton Woods agreement of 1944, and more importantly its undoing in 1971 for why the USD is a preferred trade & reserve currency worldwide. They are correct. But we will keep it for a later day. If you are interested, you can check that out along with the concept of petrodollars. Right now I want to cover the more basic reasons as to why a stable currency is needed for trade.

Now when you zoom out and find a list of commonly preferred / allowed currencies across countries, it is a very small list and the most favoured currency is just one. And that is why, most international trade is quoted in USD.

Click on the urls below the images below to view the previous and next articles in this series